Ancestor Stories: Graeme McGregor

A Descendant's personal perspective

By Graeme McGregor

MY THREE EUREKA ANCESTORS

|

The story of the discovery of gold in Victoria's central highlands and the subsequent events at Eureka are important not just for Victoria and Australia generally, but for me personally. I have three relatives who were directly involved in the conflict at Eureka, including one who was in the Stockade when it was raided on 3 December 1854.

|

Each of the three played an important part in the tragic story of Eureka. They are the brothers George and James Scobie, and Phoebe Emerson (who later married George Scobie). Over the next three issues of ‘Liberty!’ I will provide accounts of the lives of these three people.

I like to look at history in the context of the times. The 1850s must have been a bewildering time in the newly formed colony of Victoria. In 1851, with 77,000 people, Victoria became a colony in its own right, and virtually straight away gold was discovered. Migrants from around the world poured into Victoria in the hope of making their fortune, and by 1854 the population had exploded to 237,000 people (my ancestors were just three of these people). By 1861 it had reached 540,000 people, half of Australia's population. Imagine the strain this population explosion placed on the new colony. During the 1850s, the goldfields' men and women came from all corners of the globe – it was true multiculturalism with people for all sorts of societies, careers, cultures, and religions.

There is no doubt in my mind that the events at Eureka became one of the most defining events in Australia's history that were to change the nation forever – and yet the tragic short-lived battle at the Eureka stockade was a defeat for the miners, but amazingly it led to significant social, administrative and political reforms – the very things the miners sought before the Eureka rebellion. Had Governor Hotham been more conciliatory towards the miners' reasonable demands, the Eureka rebellion, with its significant loss of life, could have been avoided. As a result of Eureka, the miners' plight could no longer be ignored by the authorities. Major reforms quickly followed. Possibly the democratic reforms achieved at Eureka still form part of the freedoms we enjoy in Australia today.

I like to look at history in the context of the times. The 1850s must have been a bewildering time in the newly formed colony of Victoria. In 1851, with 77,000 people, Victoria became a colony in its own right, and virtually straight away gold was discovered. Migrants from around the world poured into Victoria in the hope of making their fortune, and by 1854 the population had exploded to 237,000 people (my ancestors were just three of these people). By 1861 it had reached 540,000 people, half of Australia's population. Imagine the strain this population explosion placed on the new colony. During the 1850s, the goldfields' men and women came from all corners of the globe – it was true multiculturalism with people for all sorts of societies, careers, cultures, and religions.

There is no doubt in my mind that the events at Eureka became one of the most defining events in Australia's history that were to change the nation forever – and yet the tragic short-lived battle at the Eureka stockade was a defeat for the miners, but amazingly it led to significant social, administrative and political reforms – the very things the miners sought before the Eureka rebellion. Had Governor Hotham been more conciliatory towards the miners' reasonable demands, the Eureka rebellion, with its significant loss of life, could have been avoided. As a result of Eureka, the miners' plight could no longer be ignored by the authorities. Major reforms quickly followed. Possibly the democratic reforms achieved at Eureka still form part of the freedoms we enjoy in Australia today.

There is another layer to the story for me, and it’s about the people who left behind the security of their homelands. Imagine the cramped conditions in the sailing ships of the time which typically took four to five months to, hopefully, reach a little-known land on the other side of the world. Was this an act of courage or madness, or an opportunity to escape the oppressive conditions in Scotland and England where my ancestors originated from? Once they were here it’s hard to imagine a harsher place to live, raise a family and make a living than on the Ballarat goldfields in the 1850s.

What my ancestors could never have realised, however, is that they would never return to their families and, quite inadvertently, would became players in the events at Eureka on 3 December 1854. This is why I so admire the courage and spirit of my great, great, grandfather and his brother who were from Scotland, and my great, great, grandmother who was from England and why I am proud to be their descendant. I find it particularly fascinating when ordinary people, like my ancestors, inadvertently get swept up in events outside their control and then rise to the challenge in which they find themselves.

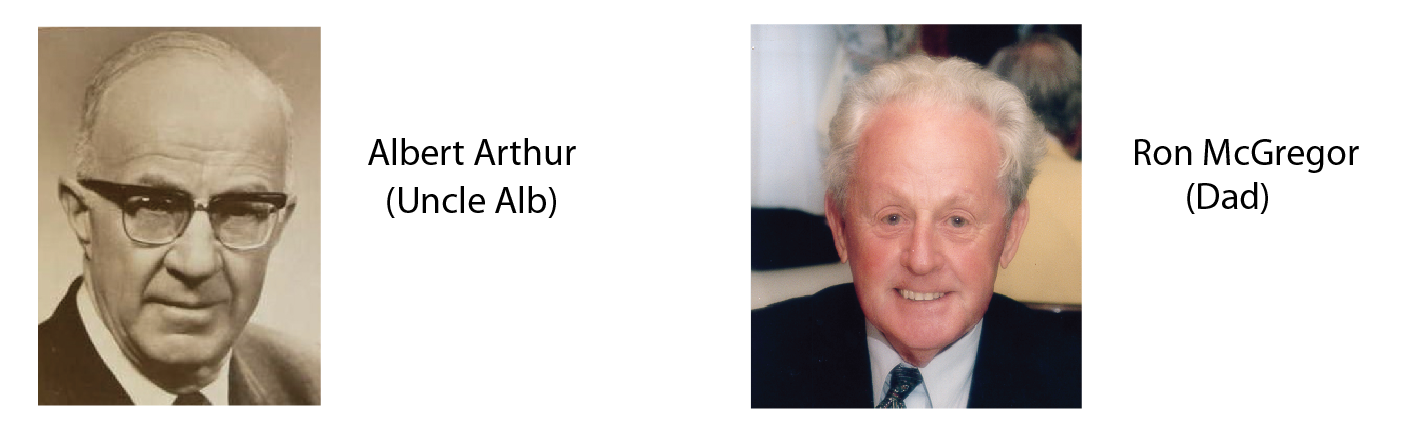

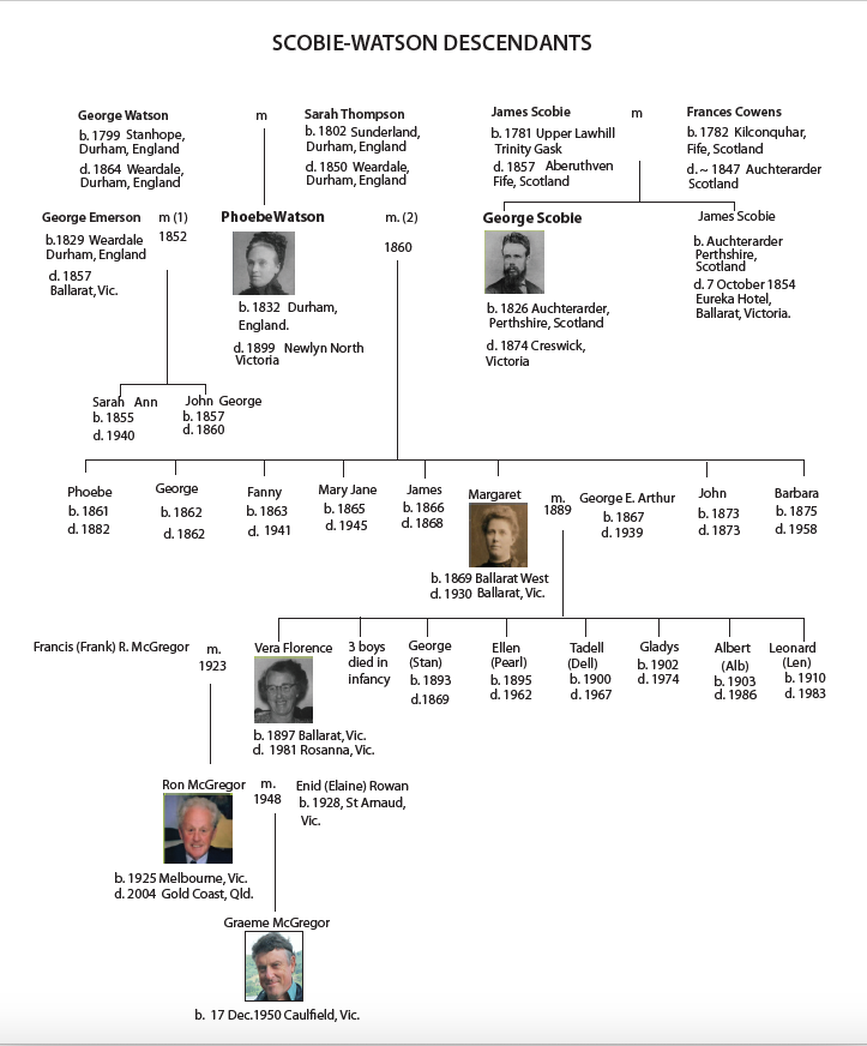

The stories of my family’s connection to Eureka were handed down to me by my father, Ron McGregor (1925-2004), who in turn obtained his interest from his uncle, Albert (“Alb”) Arthur (1903-1986). (George and Phoebe Scobie were Alb’s grandparents). We all come from the line of Margaret Arthur (nee Scobie), the second youngest daughter of George and Phoebe.

I knew that my (Great) Uncle Alb had long ago prepared a family tree but I was busy with work and family life and took only a casual interest in my ancestry. It wasn’t until I retired that I thought I would update the family tree. I asked my mother, who is somewhat ambivalent about genealogy, if she had a copy of Uncle Alb’s family tree so that I had a starting point for my research. I was told she would look for it and give it to me next time I visited. Much to my surprise when I next visited mum she presented me with a small suitcase filled with documents and photos relating to our ancestors. Unbeknown to me it was what my father had gathered, although it was a jumble of material which hadn’t been ordered and most photos were not notated. I never knew this treasure trove of material existed and now felt a greater responsibility to do something meaningful with it.

Website tools like Ancestry.com greatly assisted me in “fleshing out” my family tree and researching my past. I was becoming hooked as my ancestors seemed to “come to life” as I discovered more about them. I even joined a U3A genealogy group, meeting skilled and passionate people who assisted me in my research.

Needless to say, my ancestors’ connections to Eureka generated considerable interest in not just my ancestors but in the events at the time. I lived and worked in Ballarat during the latter half of the 1980s so I felt a close connection to the place. During my research I discovered, and joined, Eureka’s Children, now renamed Eureka Australia as I wanted to know more about this critical time in Australia’s history. I am now a committee member of Eureka Australia.

Occasionally I lead a tour which visits Ballarat and, as a tour guide, I enjoy sharing with my guests the story of the discovery of gold, the events at Eureka, and the people behind these events that changed Australia forever. It’s a story they love to hear, and it makes me proud to be a descendant of three people who formed part of the Eureka story.

What my ancestors could never have realised, however, is that they would never return to their families and, quite inadvertently, would became players in the events at Eureka on 3 December 1854. This is why I so admire the courage and spirit of my great, great, grandfather and his brother who were from Scotland, and my great, great, grandmother who was from England and why I am proud to be their descendant. I find it particularly fascinating when ordinary people, like my ancestors, inadvertently get swept up in events outside their control and then rise to the challenge in which they find themselves.

The stories of my family’s connection to Eureka were handed down to me by my father, Ron McGregor (1925-2004), who in turn obtained his interest from his uncle, Albert (“Alb”) Arthur (1903-1986). (George and Phoebe Scobie were Alb’s grandparents). We all come from the line of Margaret Arthur (nee Scobie), the second youngest daughter of George and Phoebe.

I knew that my (Great) Uncle Alb had long ago prepared a family tree but I was busy with work and family life and took only a casual interest in my ancestry. It wasn’t until I retired that I thought I would update the family tree. I asked my mother, who is somewhat ambivalent about genealogy, if she had a copy of Uncle Alb’s family tree so that I had a starting point for my research. I was told she would look for it and give it to me next time I visited. Much to my surprise when I next visited mum she presented me with a small suitcase filled with documents and photos relating to our ancestors. Unbeknown to me it was what my father had gathered, although it was a jumble of material which hadn’t been ordered and most photos were not notated. I never knew this treasure trove of material existed and now felt a greater responsibility to do something meaningful with it.

Website tools like Ancestry.com greatly assisted me in “fleshing out” my family tree and researching my past. I was becoming hooked as my ancestors seemed to “come to life” as I discovered more about them. I even joined a U3A genealogy group, meeting skilled and passionate people who assisted me in my research.

Needless to say, my ancestors’ connections to Eureka generated considerable interest in not just my ancestors but in the events at the time. I lived and worked in Ballarat during the latter half of the 1980s so I felt a close connection to the place. During my research I discovered, and joined, Eureka’s Children, now renamed Eureka Australia as I wanted to know more about this critical time in Australia’s history. I am now a committee member of Eureka Australia.

Occasionally I lead a tour which visits Ballarat and, as a tour guide, I enjoy sharing with my guests the story of the discovery of gold, the events at Eureka, and the people behind these events that changed Australia forever. It’s a story they love to hear, and it makes me proud to be a descendant of three people who formed part of the Eureka story.

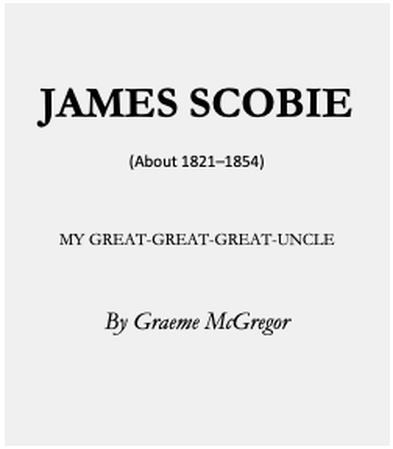

Part TWo: James Scobie

James Scobie's untimely and tragic murder near the Eureka Hotel on 7 October 1854 provided a spark that helped set the Eureka rebellion alight. James Scobie can be considered the first fatality of the Eureka rebellion[1].

James Scobie was born into a stonemasonry family at Auchterarder in Perthshire, Scotland. There is uncertainty about the year of his birth and even doubt whether he was the younger (as is generally claimed) or older brother to George.

Family legend has it that James was only a "teenager" when he departed for Australia, however, there is some evidence that suggests that he was older, possibly in his late 20s. According to family tradition, James' parents would only agree to him joining his older brother George on the voyage to Australia on the clear understanding that George would protect his younger brother from coming to harm. Their mother, Frances, died in 1847, well before her sons considered travelling to Australia. It is more likely that it was their father (James Scobie Snr 1781-1857) who insisted that the brothers look after each other.

Both brothers were lured by the discovery of gold in Ballarat. They boarded the Moselle in 1852 bound for the Port of Geelong from where they would make their way across country to the Eureka goldfield at Ballarat. James took up gold mining while George chose to establish a cartage business.

On 6 October 1854 James met up with an old friend Peter Martin and during their celebrations they had too much to drink! In the very early hours of 7 October, while walking back to their camp, the men saw that the lights were still on at the Eureka Hotel and, although closed, decided to see if they could get in, presumably for another drink. They were refused entry. A fist lunged from a window hitting James. This was followed by another punch, this time hitting Martin on the ear. Words were exchanged, and the men left the hotel. Unbeknown to them, the Eureka Hotel owner, James Bentley, his wife Catherine and two of his employees, Farrell and Hance pursued the men and hit them about the head and body with a shovel. While he was on the ground, the attackers kicked James in the head inflicting a fatal injury. Martin was injured but made his escape.

A Coroner's Inquest was quickly convened, but it was poorly, and quite possibly corruptly conducted. Witnesses for Bentley gave false statements while the witness statement of a bright ten-year-old boy, Bernard Welch, was inappropriately dismissed. The Coroner found "no suspicion against Bentley".

This incident occurred when there was considerable suppressed anger on the Ballarat goldfields over the miners' treatment by the government authorities. It wasn't going to take much to see this pent-up anger erupt.

The miners were incensed that Bentley, a former convict, had been cleared. They quickly called a gathering outside his Eureka Hotel to protest the injustice of the verdict. Bentley was known to have connections with those in authority, including part ownership in his hotel, and it was some of these people who presided over the inquest. Thousands of miners attended the meeting, and as their anger boiled over, Bentley's hotel was set alight and burnt to the ground. Now there was little chance of going back as tensions had reached breaking point between the government authorities and miners.

The intransigence and failure of Governor Hotham, a military man, to try to negotiate a settlement for the miners' demands was never going to end well. The murder of James Scobie, and the subsequent events arising from this, could be considered one of the key triggers that led to the Eureka Rebellion two months later on 3 December 1854.

Due to public pressure, a retrial was ordered into James Scobie's death. This time it was held in Melbourne. Justice Redmond Barry (who presided over Ned Kelly's trial in 1880), heard the case. On 19 October 1854, the government offered a £500 reward (a vast sum at the time), to any person who provided information leading to the apprehension and conviction of anyone involved in Scobie's murder. Now things were getting serious! This time James Bentley, Farrell and Hance were all found guilty of manslaughter and were sentenced to three years hard labour on a road gang. Catherine Bentley, who was heavily pregnant at the time, was found not guilty.

Unfortunately, James's family learnt of his murder in the Scottish newspapers before George was able to get a letter to them.They took the view that George had broken his promise to protect his brother. Family legend has it that his family excommunicated him from that day on.

[1] Ian MacFarlane (Ed): Eureka – From the Official Records, Public Records Office of Victoria, 1995, p96.

|

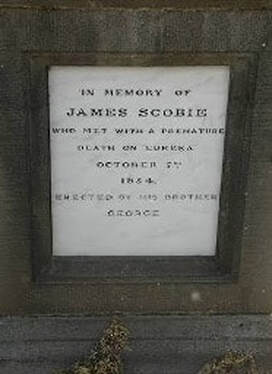

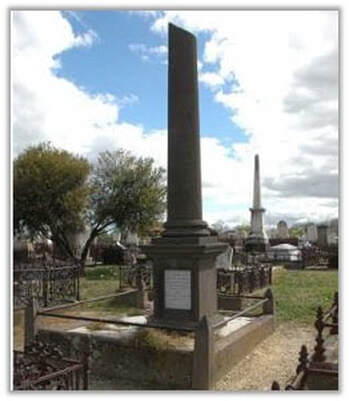

Photo: In the Old Cemetery at Ballarat you can see the beautiful grave monu-ment that George constructed for his brother, James. It is said that he built the monument over a twenty year period. George’s wife Phoebe and some of their children are interred in this grave, as well as George himself. The broken column is the traditional motif of a life cut short. The monument expresses George’s grief at losing his brother at such a young age and in such tragic circumstances. |

Part THree: PHOEBE EMERSON (SCOBIE)

In 1832 Phoebe Watson was born into a mine engineering family in Durham, England's coal-mining heartland. Her father, George, was a mining engineer as well as the official organist at Durham Cathedral.

On her 20th birthday, Phoebe married George Emerson, a shop-keeper by trade. On the following day, the newlyweds headed for the Ballarat goldfields, enduring the challenging four-month journey aboard the magnificent new ship, Ben Nevis. The fast and sleek Ben Nevis was a large three-mast barque commonly referred to as a "clipper". It is known to have made four trips to Australia; the first arriving in Melbourne from Liverpool on 3 January 1853 with 564 passengers (including Phoebe and her husband George Emerson) and immigrants onboard. Conditions for most passengers must have been incredibly cramped.

In 1832 Phoebe Watson was born into a mine engineering family in Durham, England's coal-mining heartland. Her father, George, was a mining engineer as well as the official organist at Durham Cathedral.

On her 20th birthday, Phoebe married George Emerson, a shop-keeper by trade. On the following day, the newlyweds headed for the Ballarat goldfields, enduring the challenging four-month journey aboard the magnificent new ship, Ben Nevis. The fast and sleek Ben Nevis was a large three-mast barque commonly referred to as a "clipper". It is known to have made four trips to Australia; the first arriving in Melbourne from Liverpool on 3 January 1853 with 564 passengers (including Phoebe and her husband George Emerson) and immigrants onboard. Conditions for most passengers must have been incredibly cramped.

The clipper ship Ben Nevis in heavy seas.

Oil on canvas

Artist: Henry Scott

When they arrived at the Ballarat gold fields, Phoebe and George set up a general store at Eureka serving the needs of the miners. Phoebe was widely known on the goldfields and respected for being scrupulously fair and honest in business, and willing to help anyone in trouble. George suffered from lung conditions throughout his time in Australia, undoubtedly not helped by the living conditions in Ballarat at the time.

Coming from a Wesleyan background, Phoebe did not support the violent actions mooted by the miners, but in the early morning of 3 December 1854 Phoebe's world was turned upside down with the storming of the nearby Eureka Stockade by government troops. Newspaper editor, George Black, and miner, John Humffray, two prominent members of the Ballarat Reform League, fled the carnage that ensued when the Stockade was raided. With them was the cartage contractor, George Scobie, the brother to James Scobie who was murdered two months earlier at Eureka. They sought shelter nearby in Emerson's Store. Phoebe hid the men at considerable risk to herself so the government troops couldn't find them[1].

After the battle, Phoebe's dogs began barking, and Phoebe discovered a badly wounded Peter Lalor, the leader of the miners’ uprising, in the nearby scrub. During the fighting at the stockade, a miner named Dalton hid Lalor under planks in a mine depression. Lalor remained there until the troops had left the area. He then miraculously struggled to Emerson's Store where Phoebe bound his wounds, using strips torn from her petticoat. She summoned help from George Scobie who agreed to move Lalor in his dray later that afternoon to the safety of some friends a few kilometres away at Warrenheip.

After dark, Phoebe sought help from Anastasia Hayes, one of her customers whom she knew could be trusted. Anastasia was the wife of Timothy Hayes who had been arrested. Hayes was later charged with high treason over his involvement in the rebellion. Mrs Hayes took Phoebe to Father Smyth at the Saint Alipius Presbytery seeking help for Peter Lalor. Lalor was then taken to an annex at the Presbytery where his arm was amputated by Dr James Stewart, assisted by Dr Doyle. These actions almost certainly saved Lalor's life[2].

On the following day, some government troops going past Emerson's Store found blood-stained rags and quizzed Phoebe about the find. She denied any knowledge of them. The soldiers warned her that she would be shot if found to have harboured any miners. It is quite likely that Phoebe's actions prevented the authorities from ever arresting the men. Phoebe, not yet 22 years old, performed an act of remarkable bravery on that day.

In 1855 Phoebe and George Emerson had a daughter, Sarah. In 1857 they had a son, John. On 10 September 1857,George died from a lung infection, leaving Phoebe to raise her eighteen-month-old daughter and baby son by herself. (It is not certain whether John was born when his father died). Within a few weeks of her husband's death, Phoebe sold the business and decided to return to England with her children.

With the exhaustion of the easily won surface alluvial gold it became necessary to follow the gold in the former stream beds buried beneath the basalt from nearby extinct volcanoes. This new phase of mining in Ballarat, known as deep lead mining, required underground mining expertise. Phoebe was almost packed to leave for England when a letter arrived from her brother, John Watson, an underground mining engineer, advising that he was on his way to Ballarat. Phoebe decided to postpone her departure and await the arrival of her brother. Had that letter from her brother arrived a moment later Phoebe would have left for England and, as a descendant, I wouldn't be here. She never did return home to England.

It wasn't long before Phoebe found she was being courted by George Scobie, the man she had harboured in her store after the raid on the Stockade. Phoebe would have known Scobie as he operated a cartage business, bringing stores from the Port of Geelong to Ballarat. They married in 1860, the same year that her three-year-old son John (to George Emerson) died.

George Scobie and Phoebe had six children together. Phoebe's three sons died while young; John George Emerson was three years old; James George Scobie was 13 months old, and John Scobie only six hours old when he died). Phoebe’s twenty-year-old daughter, also named Phoebe, died in 1882. Five girls, one to George Emerson and four to George Scobie, survived to adulthood, and all married.

George Scobie died in 1874 in an accident at Newlyn Reservoir, north of Ballarat. Phoebe was only forty-one at the time and pregnant with her daughter Barbara. After her husband's death, she moved to nearby Newlyn North to raise her family by herself but never remarried. She took in whatever work she could find, such as sewing, to provide the money for her family.

Phoebe, whose life had never been easy, came down with bronchitis and was ill for eight days before dying on 19 October 1899 at the age of 66. The day before she died, Phoebe wrote her will showing that she had a small landholding and house at Newlyn North, but little else of value. She is buried in the Scobie grave in the Old Cemetery in Ballarat.

One of George and Phoebe Scobie's daughters, Margaret, is my great grandmother.

[1]The Age(Melbourne), The Golden Women of Eureka (24 November 1994, p 3) and Laurel Johnson The Women of Eureka (1995)

[2]Eurekapedia.org states that the doctor who amputated Lalor’s arm was Dr. James Stewart while Dr Doyle was also present. Also Peter Lalor mentions this event in The Argus 10 April 1855.

PART FOUR: GEORGE SCOBIE

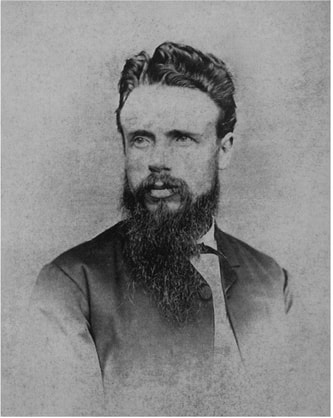

About 1828, (records show a discrepancy about George's age) ,George Scobie was born into a stonemasonry family in Auchterarder, Perthshire, Scotland. George pursued the family career as a stonemason, but in 1852 he and his brother James were so smitten by the lure of the gold rush in Victoria that they decided to travel to Ballarat, hoping make their fortune.

Family legend has it that George's family was reluctant to allow his younger brother James to accompany him to Australia. Still, the family eventually agreed after receiving an assurance from George that he would protect James. (It is worth noting that George and James's mother, Francis, died in 1847, more than four years before her sons departed for Australia so she couldn't have objected to their departure to Australia, and there is some evidence to suggest James was George's older brother)[1].

Having sailed on the Moselle, the young men arrived at Geelong in December 1852. To get their possessions to their destination George constructed a wheelbarrow. The two men took turns to push it to the Ballarat goldfields. George saw that a better opportunity than mining lay in establishing a cartage business to bring provisions from the Port of Geelong to the miners at Ballarat. James helped with the business but he was also a gold miner.

On 7 October 1854 tragedy befell the Scobies when James was killed outside Bentley's Eureka Hotel by publican James Bentley and two of his employees, Farrell and Hance. This tragic event was also to irrevocably change George's life because George's family in Scotland believed that he had broken his promise to protect James. This resulted in a rift in the family, with George being treated as an outcast from then on. His connection to his family in Scotland was never restored.

James Scobie, who was known to the miners as ‘Scottie’, was a popular young man, and his murder enraged the miners. They were even more enraged by the initial acquittal of James Bentley despite strong prima facie evidence implicating him in the crime. They gathered in their thousands at Bentley's Eureka Hotel to protest the unjust findings of the Coroner's inquest into James's death. Before the day was out the miners had burnt the Eureka Hotel to the ground. It had been the grandest hotel on the Ballarat goldfields. Following public pressure, a trial was ordered. This time, James Bentley, Thomas Farrell and William Hance were found guilty of the manslaughter of James Scobie. Bentley's wife, Catherine, was found not guilty.

Thousands of miners gathered for a mass meeting. There was great sympathy for George over the loss of his brother, and much anger at the failure of the authorities to investigate the murder of James properly. This may explain why it was that on that fateful morning of 3 December 1854, George was in the Stockade at Eureka when the government troops raided it. In the carnage that followed the unexpected raid, some of the miners in the Stockade fled for their lives. George Scobie as well as two others who supported the miners’ cause, George Black and John Humffray, sought shelter in the nearby store run by Phoebe and George Emerson. Shortly afterwards, Phoebe found that the miners' badly wounded leader, Peter Lalor, was hiding in the shrubbery near the store. At great danger to herself from reprisals by the government troopers, Phoebe hid the men and tended to Peter Lalor's wounds.

It is likely that George Scobie would have known Phoebe Emerson through his cartage business, as he may have brought goods from the Port of Geelong to her store. Phoebe sought help from Scobie to take the injured Peter Lalor on his dray to a place of safety at nearby Warrenheip, while she summoned help for Lalor. After securing support, Lalor was taken to an annex of the Saint Alipius Presbytery of Father Smyth where his shattered arm was amputated on 4 December 1854. Scobie reputedly then took Lalor, concealed in a load of Patrick Carroll's farm produce, to Lalor’s fiancée Alicia Dunne and friends in Geelong where he recuperated[5].

The courageous actions of Phoebe and George, and the doctors who tended to his injuries, saved Peter Lalor’s life.

Phoebe was first widowed in 1857 when her husband, George Emerson, succumbed to a lung infection. In time George Scobie began to court Phoebe and in 1860 they married. There were six children to Phoebe's second marriage to Scobie as well as her two children to George Emerson.

George Scobie fell on hard times with losses in mining and contracting, and was declared insolvent in 1863. He went back to stonemasonry, working on some bridges and local reservoirs, including Newlyn Reservoir, where he later became the caretaker.

During a flood in 1874, George operated one of the reservoir valves, presumably to release some of the floodwaters. It blew up, causing terrible injuries from which he died four days later in Creswick hospital. George Scobie was about 45 years old, leaving behind a young family, with the youngest child born two months after his death.

To honour his brother's death, George built an impressive monument over James' grave in the Old Cemetery at Ballarat. It has a broken column as its centrepiece (see the picture in James Scobie's chapter), which symbolises a life cut short. Working on the gravestone when he had time, it took George 20 years to complete, finishing it only one month before he was killed in an accident in 1874. He is buried along with his brother James and other family members.

George was never to return to Scotland, however, he and his wife Phoebe have left a long line of descendants in Australia, one of whom is me.

[4]There are details in both the family’s versions of events, and the commonly held view found in publications and the internet which I believe are not backed by evidence (or where no evidence can be found). One such example is the age of James Scobie.There is some evidence, such as the shipping records (not always considered to be accurate), to support that he is George’s older brother and was probably in his late 20s when he come to Australia. These versions are of interest and invite further research.

[5] Bob O’Brien: Massacre at Eureka: The Untold Story, 1992, p 125.